Hillel O’Leary

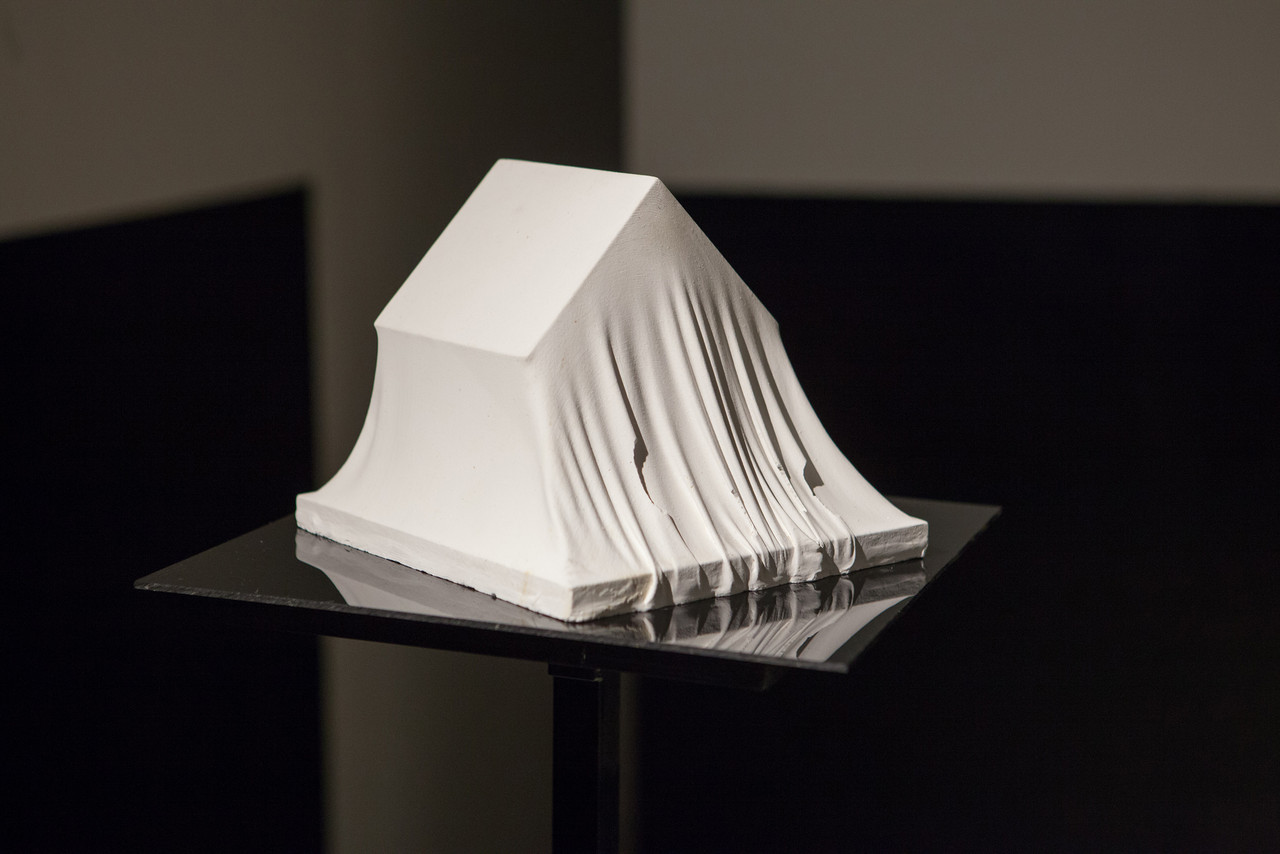

____ is where the _____ is, 2021, Cast plaster, Courtesy of the Artist.

Visit Hillel O’Leary’s website

Instagram: @HillelOLeary

Hear from the Artist

Transcript

Hello, My name is Hillel O’Leary, and the work I’m exhibiting in the Newport Biennial is called ____is where the _____is.

The title of this work is an adaptation of a phrase often attributed to Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder, it was meant to convey a longing to return to a sacred and special place, when one had traveled far away.

It represented a homesickness for a place of personal history and belonging.

It has since been adopted in a number of romanticized and kitschy ways, including that cozy needlepoint that hangs on the kitchen walls of loved ones, usually more earnestly than ironically.

I have thought about this idea of belonging somewhere, and feeling safe for my entire life, and I wanted to capture the tension between the promise of the warm and safe feelings of home, and the stark contrast of not really ever having that experience for most of my life.

I grew up on Long Island, the epicenter of the mass-produced suburban boom. My family was poor and Jewish, and when my parents bought our first house, there was a swastika scrawled inside of it.

They didn’t tell me until I was an adult.

In these suburbs people had returned from a terrible war, and they wanted safety. For them, that meant homogeneity . There was comfort in the sameness, which further vilified anyone who was different.

Their safety became my ever-present danger.

For me, that has meant enduring poverty, bigoted violence, and the constant vigilance that comes with having to fear all the time

I’m part of a diaspora culture, Which means that generations of my family bear this same burden of having to flee somewhere that they used to call home, and it means that somewhere there is always a sense that they don’t belong, or that they are not worthy of peace

People in these cycles also often perpetuate the harm they have suffered by inflicting it on others, including their own family members. These cycles create harsh narratives in one’s mind about their worth, their identity, and about what they deserve.

These narratives become enmeshed in one’s sense of self, and become a fixed point in the strata of intergenerational trauma. This stuff sticks around, and makes you believe you don’t deserve to have a home

I spent much of the last decade struggling to find a place where i felt safe, and that meant living in cars, in closets, or tents. I didn’t think i deserved any better. My earliest community taught me that.

My story is one of a great many in the continuum of American stories that center on a lack of safety, and a lack of housing security.

This work is a reflection on the idea that the American Dream of home is not real for so many people because of white supremacy, classism, and systemic issues of inequality.

The form and stark white are meant to call upon western art historical monuments, and are meant to link our adherence to westernized history to these issues.

I hope to invite people to consider their own place in this cycle, and to think about how important it is to hope for, but also work for a place that everyone can call home.